Abundance by Brandon Graham, Illustrated by Hannah Batsel

My mother’s father would take me to a cabin to fish in the summers. What I remember is a steep dirt track with branches brushing the Scout as we dropped down to a secret lake. A short dock left to rot, a decent metal johnboat facedown and overgrown with tall grass.

My grandfather beat the boat with an oar until snakes slithered away, a few cutting curly waves across the black water as they escaped, like a slick signature.

He flipped the boat. We filled it with tackle and rods. He clipped a new, stiff, life preserver around me. My mother made him promise I’d wear it.

I got in the front of the boat. He shoved us off and stepped in the back, nearly pitching me out. We cleared the wild green growth chocking the bank on all sides and slid out.

The air was rich with organic smells and hard to breathe.

It was Virginia and hot. Lots of insects—horse flies and deer flies always trying to sting through the top of my cap; dragon flies, too, zipping along beside the boat as we cast our rods. I loved to watch them land on the tip of my rod as I waited for a nibble.

We saw lots of wildlife. Beavers dammed up the place where this lake would spill its bank and form a creek that ran down to a small pond deeper in the woods.

Once, a beaver was angry and it cut through the water, aimed its head at us like an oily torpedo and before it rammed us it dove under, flipped around, and smacked its tail against the lake’s surface. It cracked like a shotgun going off beside me. I jumped. My grandfather laughed in a kind way. I decided to feel excited instead of scared. There was a tree fall covered with terrapins that plunked, one after the other, into the deep water as we fished closer.

In the distance we heard baying hound dogs coming nearer.

“One of the farmers let his dogs out and they’re running a deer.”

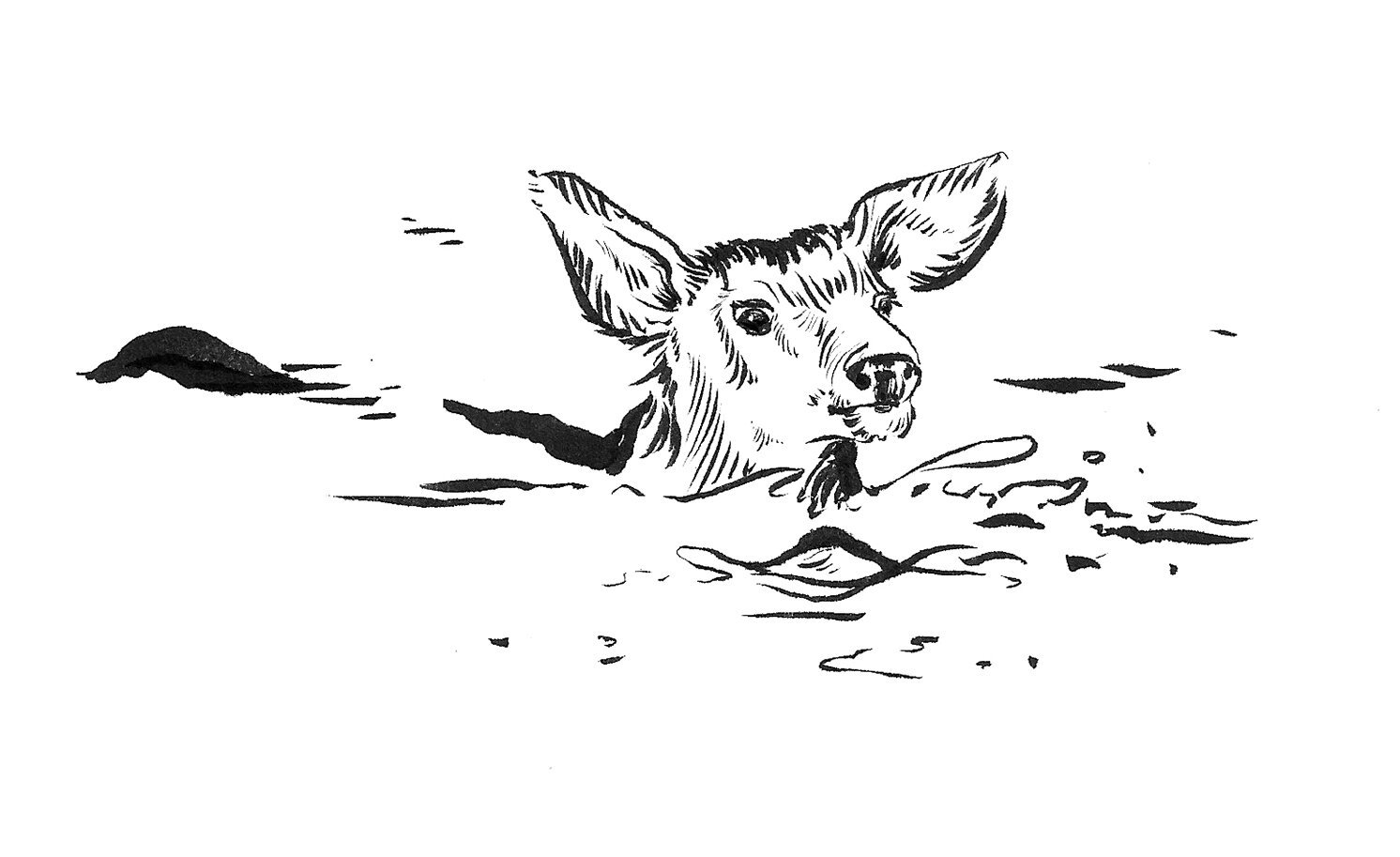

I didn’t doubt what he told me. The sound got closer and closer until a deer burst through the greenery and landed in the lake, its front legs churning water, its head held above the surface and completely still, regal but with wild eyes and foam around its mouth.

The barking was frantic and loud and beat on my ears and three dogs took long leaps off the bank and started sloppily splashing after the deer. It happened fast.

I sat there in the boat, my sore, boney ass no longer a concern, unaware I was still holding a fishing rod, too riveted to do more than give a sidelong glance at my grandfather.

When I looked back, the deer had turned around. It swam right at the dogs now, plowed them under with its sharp front hooves. The dogs yelped and were gone.

In the comparative silence, the deer panted loudly as it worked to reach the bank. It slowly found its legs in the shallows and limped out of the lake, exhausted and dripping wet, sides heaving. It disappeared back into the woods.

My grandfather said, “We’ll have to go by the Stevens’ place and let them know their dogs are dead.”

We didn’t go near the end of the lake where the dogs were bobbing on their sides. Right then I caught a fish so big my grandfather had to creep up the boat and help me lift it in.

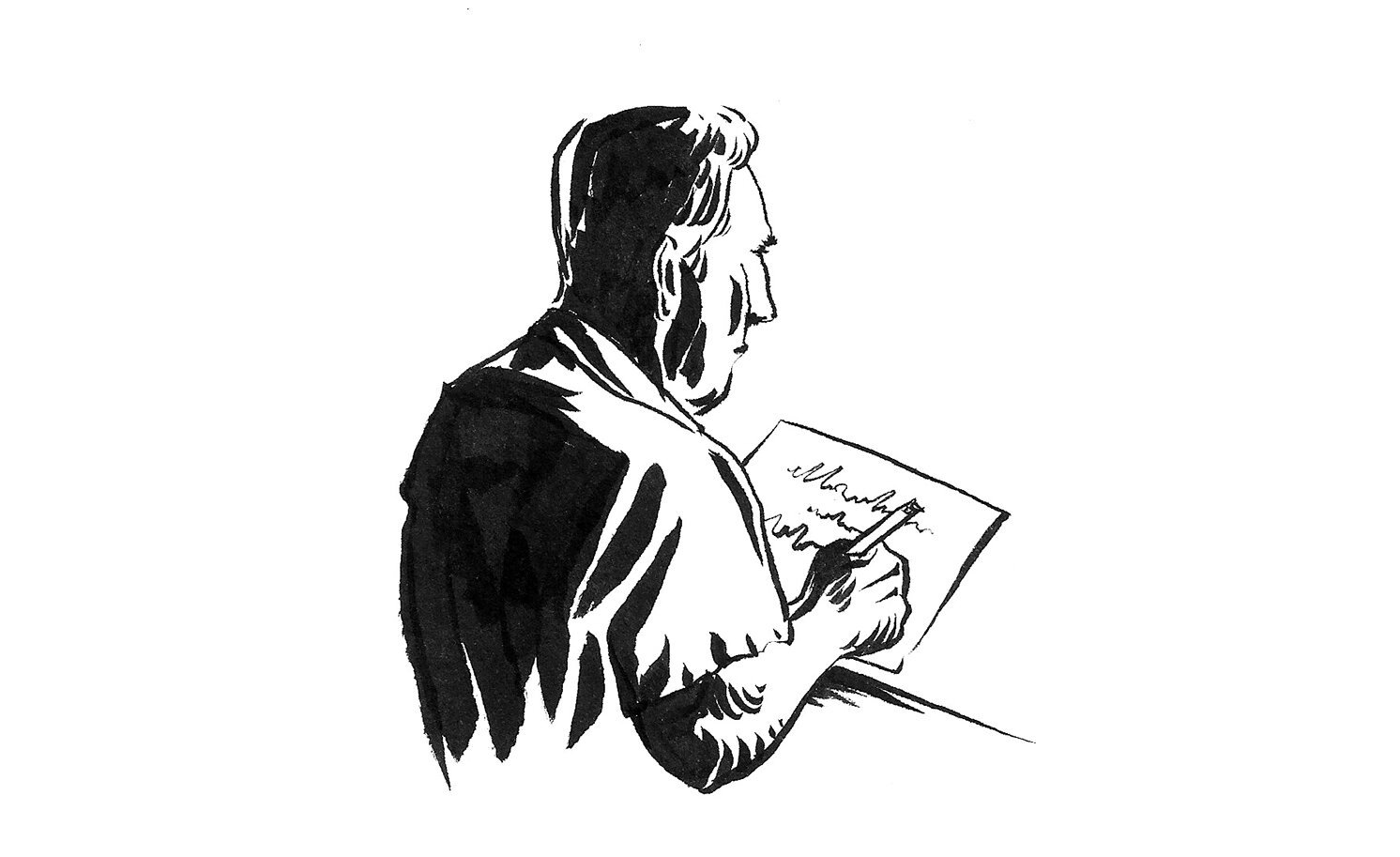

My Grandfather was a judge, and when we got back, he had an official decree drafted like a diploma on parchment paper, which he signed and stamped.

Something like: “I hereby swear that on such and such a day B. Scott Graham at the age of only five years old did catch a large mouth bass weighing such and such.”

Truth is my grandfather didn’t say much to me other than to give fishing tips. I used to think he was a quiet man, but now I realize: what the hell kind of conversation were we supposed to have?

He was about to retire after a stint in the Pacific during WWII, law school, a marriage, divorce, another marriage, and a long career in law. I mean: we didn’t have much in common.

I was five and liked hide and seek. But he smiled at me often, nodded his approval while we spent long stretches drifting around the lake, listening to the wind in the trees.

Once in a while I’d dangle my fingers in the cool water. The quiet and calm and the water and the wind combined to teach me that being outside and feeling myself belong to nature can be overwhelming and calming.

Now, I think it gives my worries perspective and offers sensations to soothe the primitive parts of my brain. It’s why drifting on a river in Northern Michigan has become my favorite thing to do.

It’s why I daydream of a little place on any kind of water. I think it will quiet my mind, it will offer me peace.

You know: there is a primal part of the brain that links us back to our evolutionary past, and I guess it tells us running water means we are safe, because we have a thing in abundance that we need.

I get a similar feeling in my body watching a campfire.

I might add: our reptilian brain is at the top of the spinal column, and the mammalian brain, a bit bigger and right on top of it, in combination, are called the Limbic system.

It’s where our hormones are regulated. If you make those primitive pieces feel satisfied, it bypasses our over-thinking and high-functioning cerebral cortex.

It signals wellbeing despite what we may be worried about. It’s how being in nature can feel meditative. It’s a cheat that enables us to ignore our own busy minds.

Maybe. I’m not really sure. But it feels like it’s true.