Birds Fall Like Rain By Evan Silver, Illustrated By Deborah Lader

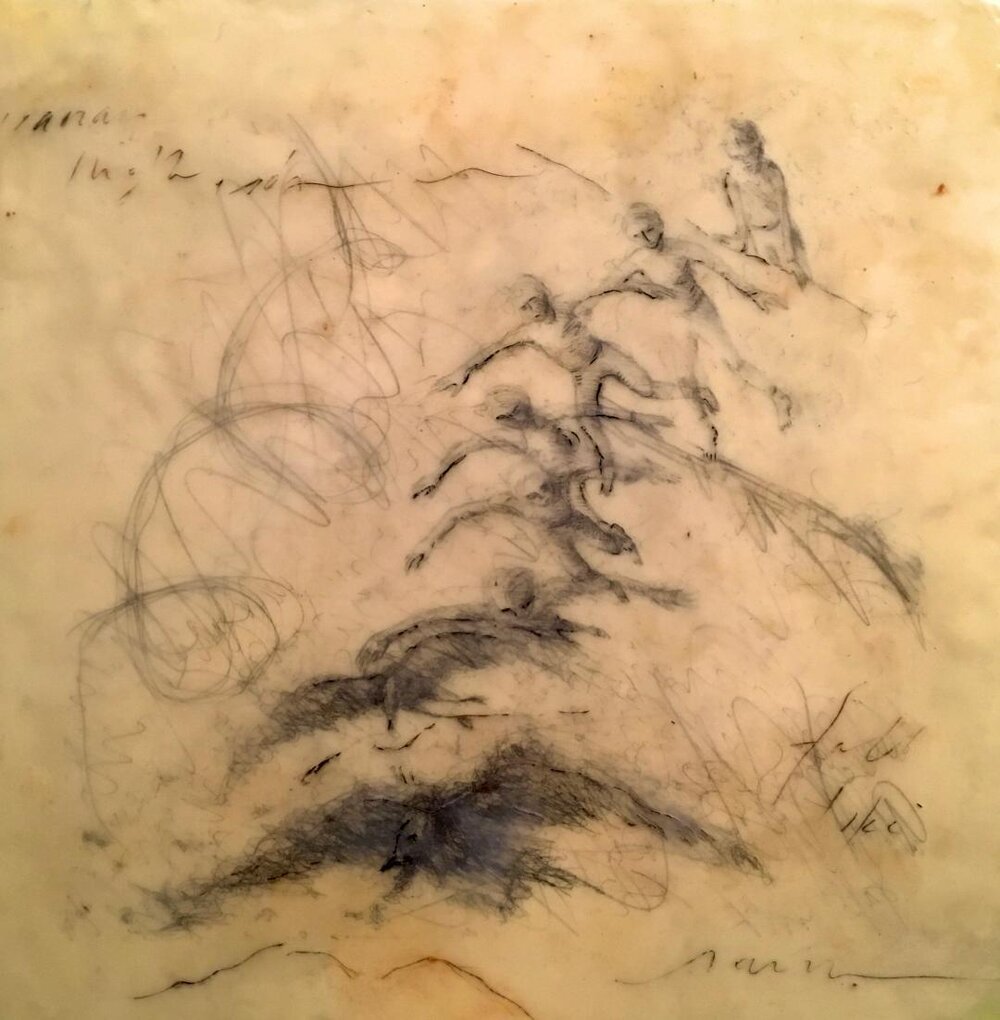

The moon conceals herself beneath a mask of sky. A tireless wind tears rust-stained rice-paper leaves from autumn pines. The sun sets in Jatinga, a small cliff-side village on an Indian plateau. Tonight, birds fall like rain.

Every year near the end of the monsoon season, large numbers of herons, hawks, bitterns and egrets crash into the village of Jatinga in ‘mass impacts’. The birds that survive are found dazed but at least not dead. They do not attempt to fly away when approached. The birds are fragile.

The villagers have been known to capture the injured birds with bamboo poles and then beat them to death, believing the birds to be evil spirits terrorizing the village. While conservation efforts have reduced the number of killings, the village is still widely referred to as ‘the valley of death for birds’.

The phenomenon, which has piqued the interest of ornithologists worldwide, is yet to be fully understood. Many scientists hypothesize that the birds are disoriented by a combination of high altitudes, high velocity winds, fog and mist, and redirect themselves toward the lights of the village, crashing into trees and other obstacles along the way. The journey to the doomsday light, then, is the tragic downfall of these displaced Icarian moth-gods.

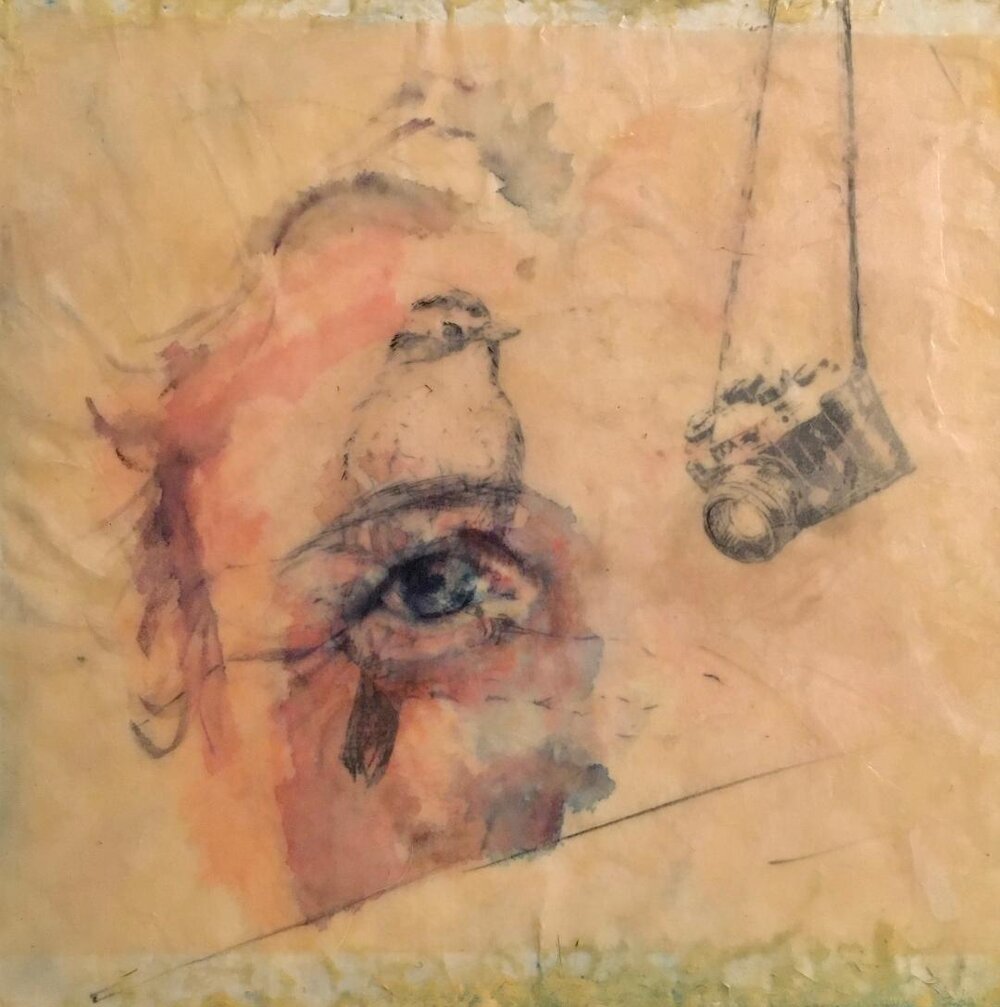

A recent story in the New York Times investigates the mutual healing that occurs in a work-therapy program at Serenity Park in LA between abandoned parrots and war veterans suffering from PTSD. At Serenity Park, patients and parrots alike nurse the wounds of trauma. In the words of Lorin Lindner, the psychologist who founded the program, ‘The parrots get what the veterans are going through and, of course, the veterans get them, too, because, hey, they are all pretty much traumatized birds around here.’

A former Coast Guard rescue swimmer with severe PTSD finds hope alongside a disheveled cockatoo who spent most of her life in a kitchen drawer. A former yeoman who witnessed traumatic violence in Bahrain finds a kindred spirit in an altruistic yellow-headed Amazon named Joey, who selflessly raised two birds of another species at the sanctuary from infancy to adulthood.

The bonds forged at Serenity Park are a testament to the reparative potential of interspecies empathy and compassion. Veterans feel empowered to access and confront their own trauma through the parrots, who demonstrate an enormous capacity for complex social thinking and awareness. Many of the abandoned and traumatized parrots exhibit symptoms virtually indistinguishable from veterans with PTSD: rapid pacing, distress calls, self-mutilation, nightmares, insomnia, aggression in response to physical contact. In the eyes of the parrots, veterans at Serenity Park see mirrors of themselves, and by taking care of the parrots, pave their own paths to healing.

‘You look in their eyes, any of these parrots’ eyes, and I myself see a soul. I see a light in there. And when they look at you, they see right into your soul,’ one veteran explains. Perhaps empathy is not a skill but a ‘neuronally ingrained bioevolutionary tool for survival...the ability to inhabit the feelings of fellow beings’. Why should such a strategy be limited to human creatures?

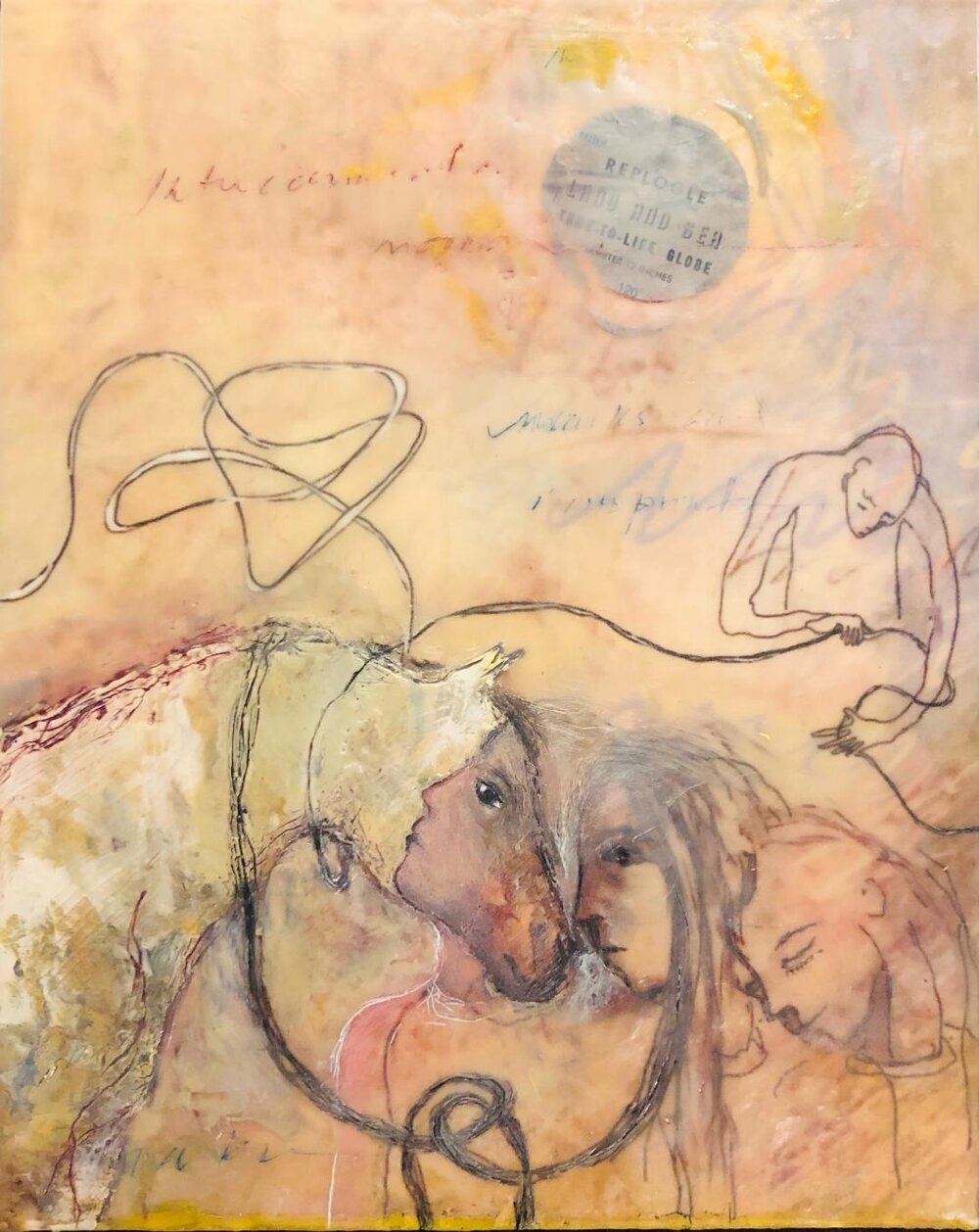

Moxie sees me before I see Moxie. When I fall upon him staring at me, with his quiet intensity and unwavering focus, I am suspended in time. Those big, shiny, black marble eyes, like planets around which revolve discrete but interconnected moons. He is a cautious horse: who am I, what to think of this visitor. He peers into my uncertain, helplessly anthropomorphizing soul.

Connie, my theatre professor and friend, took me to the farm last week. When I watch her interact with the horse, I am captivated by what seems to be her complete attunement to the horse’s energy and body language. Moxie’s ears and eyes shift slightly. ‘He’s thinking about his friend Rambo.’ Rambo is in the barn, not presently visible. Connie gently but sternly moves Moxie’s face away from the direction of the barn. Holds it for a moment, until Moxie’s focus shifts, softens suddenly. ‘Now he’s back here, with us.’

Today, Moxie is calm, but Connie has warned me to be careful. Moxie is a nervous horse, and has the potential to become suddenly unhinged. Connie explains that Moxie’s previous owner, a former helicopter gunner in the Vietnam War, is very rough with his horses, and that, as a result, his horses develop nervous and even neurotic dispositions. Rather than confront and reckon with his severe post-traumatic stress, Moxie’s previous owner attempts to repress it. He tries to eclipse the sensitive area with a mask of tough-guy cloud-cover, what Connie calls his ‘swagger’. Wouldn’t want to be a lost little bird and run into that guy.

Connie assures me that horses remember everything; an act of aggression is internalized and stored somewhere in Moxie’s cells. Like squawked broken-record echoes of past abuses and nightmarish flash-backs of grisly memories, traumas leave behind marks and imprints.

Aristotle understood the soul to be the animating principle of every living thing, including plants, animals, and human beings. The souls of plants, he argued, posses three essential powers: nutrition, growth, and reproduction. The souls of animals include the fourth power of sensation, which also encompasses desire and aversion. Humans, so Aristotle believed, possessed two additional powers: intellect and will.

If a parrot has the cognitive capacities of a five-year-old human child, does not a parrot possess intellect? If a person with a severe developmental disability has the intellectual capacities of a parrot, does that class him any less human? Surely not. Parrots are robustly intelligent creatures with the capacity for complex problem-solving, episodic memory, theory of mind, abstract thinking, and sophisticated social awareness. They also utilize and comprehend language. Not only our language, but their own.

How do we define ‘will’? According to Aristotle, will is a form of appetite, in which action accords with both calculation and choice. It is a faculty of the mind which makes decisions by selecting the strongest desire from various options. Within the field of philosophy, will is considered central to ethics and morality because it motivates deliberate action.

Moxie observed and made a calculation: I was a friend of Connie’s. I did not seem brash or threatening. I was approachable and potentially even trustworthy. Perhaps Moxie could ignore me altogether. Perhaps there might be positive reinforcement for a positive encounter. From a range of possible actions and desires, Moxie made a choice to move closer.

Icarus wears wings his father Daedalus built him from feathers and wax. Daedalus warns him of both hubris and complacency, advising him not to fly too close to the sun nor too close to the sea. The brash and enthusiastic Icarus ignores his father’s instructions and loses himself to the ecstasy of flight. He flies too close to the sun. His wax-wings melt, and he plunges into the sea, doomed bird that he is.

There are over sixty species of birds that cannot fly, including ostriches, emus, cassowaries, and penguins. For these birds, natural selection has favored alternative biological advantages, such as swimming in penguins and a deadly knifelike middle toe in the formidable and fiercely glamorous cassowary, whose eggs look like overwrought emerald-colored renderings designed for a high-concept animated fantasy fairytale flick. Not all birds need wings.

In fact, flight muscles come with a cost. Even when not in use, large wing muscles require a great deal of energy to maintain. Evolutionarily speaking, smaller flight muscles are favored when larger ones are not necessary for survival. Given that this is the case, flying is not a binary of flight vs. flightlessness but a full spectrum of abilities.

When wings no longer flutter, whether as the result of evolutionary trial-and-error, high altitudes and whip-like winds, the scorching heat of the sun, or the traces of trauma in memory, there are alternative modes of living. There are other ways of being. We can, perhaps, find light in the eyes of other living things, or choose to love broken things. We might learn how to read souls or grow ostentatious with egg-laying. Birds fall out of the sky. It is perhaps our task, then, to tend to our wounded and let them tend to us in turn. And if it is such that we may never fly again, well, glory be to god for cassowaries.