January 2021

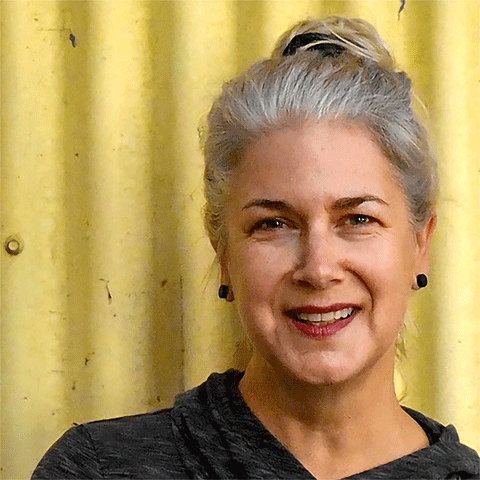

By Jamie Lou Thome

A few years ago, a novel came across my path with an intriguing title (Sweet Lamb of Heaven) and an even more intriguing cover (white fur undulating beneath black and red letters that are slightly visually jarring, a bit disoriented). I remember that I gulped that book quickly, relishing it, seeking out more work by its author, Lydia Millet.

Millet’s work is difficult to describe, as is deftly balances between sharply observant and sharply funny, elegant and dark. In 2010, her collection of short stories Love in Infant Monkeys was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and last December, The New York Times declared Millet’s A Children’s Bible one of its 10 Best Books of 2020.

When I picked up A Children’s Bible shortly after the New York Times announcement, I was struck again by the elegance and humor and pathos in her writing, and reached out to her with some questions which she quite kindly and generously answered. Here is our email conversation, unedited.

What were your reading habits as a child? What book(s)/stories shaped you and inspired you to become a writer?

First I loved Dr. Seuss. In general, books about magic and animals that talked. Narnia, Edward Eager. And a lesser-known series I adored by Beverley Nichols, a trilogy called The Woodland Fantasies written in the 1940s, called The Tree That Sat Down, The Stream That Stood Still, and The Mountain of Magic. Read them if you can find them—the first one has been reissued, but I’m not sure about the other two. My copies are almost in shreds.

What books have you read as an adult that you consistently recommend that others read (and why)?

Thomas Bernhard, but a thousand writers will tell you that. Due to his tone and sentence structure, though he wrote in German. Lydia Davis, due to her genius. I’ve laughed a lot at Julie Hecht and Lynne Tillman. For depressed people and particularly the friends of depressed people, who don’t really know the difference yet between depression and sadness—which is how it first came to me—Darkness Visible, the William Styron memoir. And Lucy Grealy, Autobiography of a Face.

What books have you read recently that you wish you’d written?

Earlier this year, Caspar Henderson, The Book of Barely Imagined Beings. Right now Thin Places, essays by Jordan Kisner. I started reading them because I talked to her for a podcast and thought she was a freakishly good conversationalist. And I do wish I’d written them. I deeply admire her insight and empathy and the capacity she seems to have for spending time with people without needing to find sameness in them.

When you feel like you’ve lost inspiration for writing, where do you go to find it again?

I haven’t felt that way yet. I dread the day.

There is magic present in a lot of your work, though your work is realistic/literary fiction. How do you figure that part out when you’re writing? How do you decide to add the magical elements? When is it “okay” to set up a spiritual/magical premise and when is it not? In other words, how do you give yourself permission to do so in an otherwise ‘realistic’ story?

I see magic in literature as just an extension of metaphor. From the somewhat plausible to the less plausible. So when a character or event seems called for that’s more symbolic and less familiar than the constructs that are already there, I let it be an outlier. Preposterous or anomalous. Some kinds of readers are bothered by that—the intrusion of heterogeneity into a text that’s supposed to be homogeneous. The mixing of degrees of separation from the real. One novel I did, Mermaids in Paradise,had a sudden deus ex machina at the very end—I still see disgusted reactions to that crop up among readers now and then. Indignant. It’s as though you’ve tricked or gaslit a reader, shortchanging them with sleight of hand.

Honestly I’ve felt that way too as a reader: sometimes an absurd or magical element looks exactly like a copout. For me as a reader, it’s usually when a book ends up like the TV show Lost: that is, lost. In the sense that it never completes the circle, never fulfills the mystery it promised. Never reveals a wizard behind the curtain that would justify its painful buildup of suspense, its mysterious codes and elusive clues. Instead, it ends with no codebreaking at all. There never was a code, only a bunch of cool-looking squiggles the producers or writers felt like making. No mastermind, no meaning, no puzzle—just style.

For myself I need to have a sense, as I watch or read and certainly when I finish, that there’s a lucid intent behind a story. But for some readers the bar is even higher: they don’t want to see an object that doesn’t seem to belong, period. Even if there’s a compelling reason for it to be there.

It’s clear in your recent novel A Children’s Bible how your work with the Center for Biological Diversity influences your fictional writing, as it centers on natural disaster(s) causing upheaval in the central characters’ lives. How does the inverse work? How does your being a fiction writer influence your work in your full time job?

Being able to spend part of your life imagining whatever you want is great luck. Great luxury. I’m able to focus better, I think, on my editing job knowing I’ll have a furlough from its reality later.

Walk us through your process, from seed of an idea to manuscript completion. How do you balance full time work with writing? What is it about writing that brings you joy?

Sometimes there’s not much balance, such as when I have to drive my children to school and then go straight into my day job. The shelter-in-place life has been good for me in that one regard—the part where I don’t have to drive so much. So I can write for an hour or so in the morning and at night.

About joy. I like not knowing what I’ll do next. The newness of it all the time. Our brains are wired that way, I guess.

What advice did you receive when you were just starting out as a writer that continues to resonate? What advice would you give to someone who is new to writing fiction?

I would say read a lot, and read categories of things you haven’t read before. And also, try not to be internally defensive about criticism of your work. Try not to let your guard go up against the criticism because it hurts or offends you.

Unless it’s being offered by someone you share no taste with. In that case, still don’t be defensive, just be polite and then completely ignore it.

Thank you! I’m so grateful, and feel very lucky and honored that you took the time to answer these.

The questions were a delight!

Lydia Millet BOOKLIST:

Omnivores: A Novel (1996)

George Bush, Dark Prince of Love: A Presidential Romance (2000)

My Happy Life (2002)

Oh Pure and Radiant Heart (2005)

Everyone's Pretty: A Novel (2005)

How the Dead Dream (2008)

Love in Infant Monkeys (2009)

Ghost Lights: A Novel (2011)

Magnificence: A Novel (2012)

Mermaids in Paradise: A Novel (2014)

Sweet Lamb of Heaven: A Novel (2016)

Fight No More: Stories (2018)

A Children's Bible: A Novel (2020)